“What It Means to Be a Black Fashion Designer”

It seems like every week a fashion brand is rallying behind a political candidate, collaborating with a nonprofit, or announcing a new sustainability initiative—in other words, companies are trying to prove they are more “conscious.” Being “conscious” has become a talking point. Credit the current political climate or the idea that customers want to shop their values, but more and more designers are being vocal about where they stand on certain issues, and companies are increasingly transparent about their business or manufacturing practices.

It’s a positive development in an industry that is known for secrets and elitism. But long before these conversations were considered “on trend,” black women working in fashion in different capacities—designers, models, stylists—have advocated and worked toward making fashion a more inclusive, representative space.

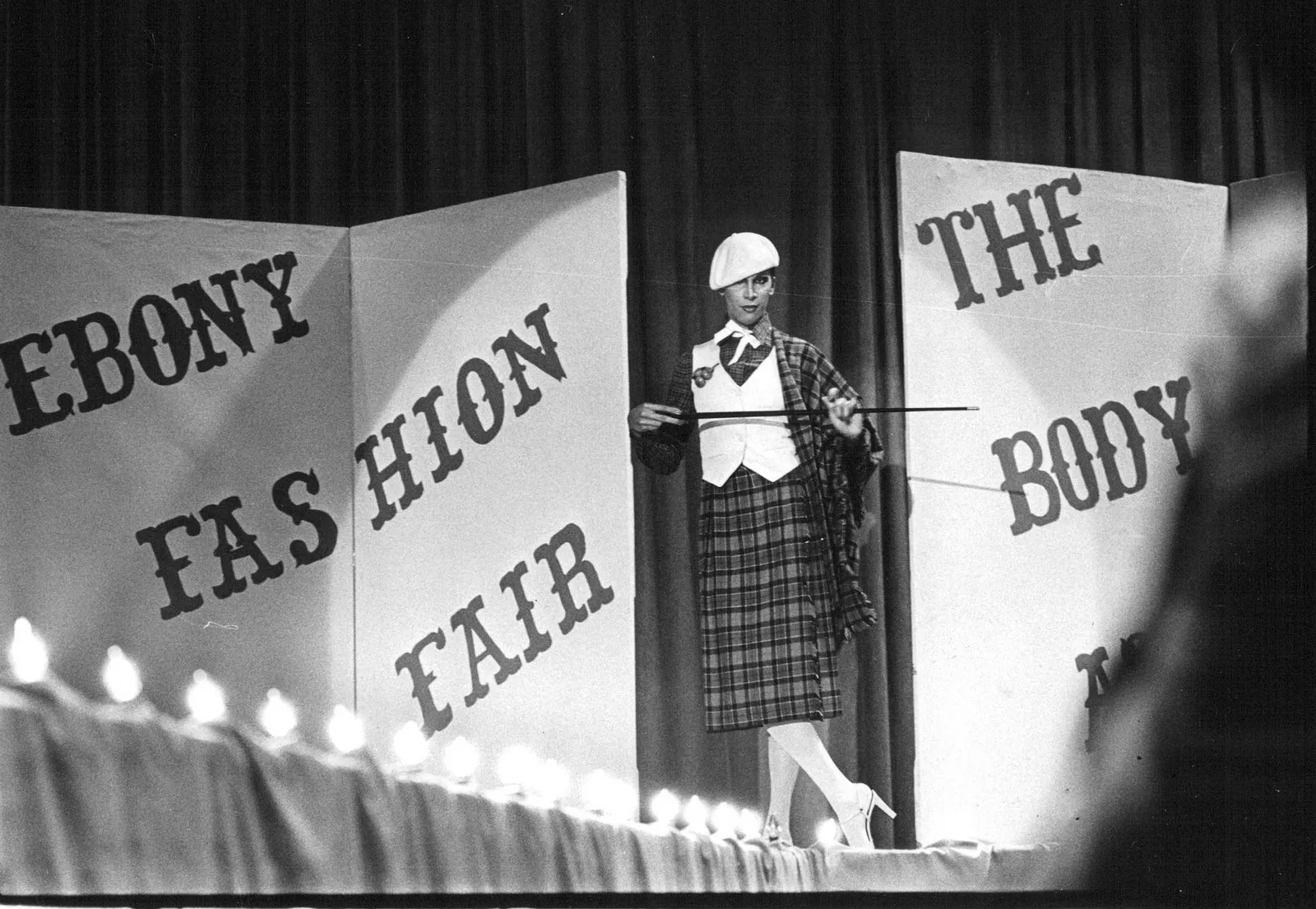

Ann Lowe, the woman who made Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress, carved a path for herself, becoming the first black designer to open a boutique on Madison Avenue, and paved the way for many others. (Finally, people are recognizing it.) From 1958 to 2009, the Ebony Fashion Fair, founded by businesswoman Eunice W. Johnson, created a space not just for black designers and models to show their work, but also for black shoppers to spend. By the early 2000s brands like Baby Phat were introducing products to the market that addressed the needs of this previously underserved customer, like jeans that fit curves.

Fashion still has a lot of work to do when it comes to diversifying its talent pool. In February 2015 only 2.7 percent of the designers on the New York Fashion Week calendar were black, according to The New York Times; by February 2018 that statistic was still under 10 percent, per The Cut. And there have been regular reminders of why this is critical: Designer products resembling blackface or nooses have sparked calls for boycotts and increased demands that companies take steps to diversify and educate their employees and provide new opportunities for people of colour. Amid the headlines and outcry, black fashion designers keep doing the work: creating and advocating for more inclusive fashion through their products and every single facet of their business.

There are women like Lizzy Okpo, who founded the women’s wear brand William Okpo with her sister, Darlene; Aurora James of the mega-popular accessories label Brother Vellies, which has been spotted on Tessa Thompson and Beyoncé; and the up-and-coming Shanel Campbell of Shanel, a recent Parsons graduate who has already dressed Tracee Ellis Ross, Ciara, and Solange. For them, being “conscious” isn’t an afterthought—it’s what drives them as artists.

That doesn’t mean the work is easy. I recently founded my own business, The Folklore, an online retail concept store that stocks brands exclusively from Africa and the African diaspora. Already I’ve had to defend the earning potential of African designers to prospective non-African venture capitalists and investors, who were convinced that they wouldn’t sell well among non-African audiences. (Most of the pieces on my site have sold out.) I’ve argued against long-standing stereotypes that paint Africa’s business climate broadly as corrupt. I’ve invested my own money to launch the company, trusting that my vision will translate.

Seeing people like Okpo, James, and Campbell succeed by remaining steadfast in their beliefs and working to make this industry better gives me hope, yes, but it’s more than that: It gives me a road map. Here, Okpo, James, and Campbell detail how they integrate their social-political beliefs into their fashion—and why other designers should do the same.

“If we’re not challenging each other to think outside the box, then what’s the point of creating art?” —Aurora James, founder of Brother Vellies

On Brother Vellies’ mission

“Brother Vellies came from this idea of reclaiming a shoe that was traditionally African but had sort of been readapted in people’s minds as a British shoe. And it’s not. The brand was born out of that and that social mission—the goal of educating people about what traditional African attire is and can be.”

On mixing business and politics

“When things shifted politically a few years ago in the U.S., it was important to me to I speak out, because I could see that a lot of marginalized communities were going to be affected, including several of the communities I’m a part of. I felt that as someone with a platform—albeit a small one—it was still my responsibility. Still, every week, we upset people.”

On pushing the envelope

“I do get nervous from time to time. There are images that we put out on our social media that I’m like, ‘Wow, is this kind of heavy for a shoe brand?’ But heavy is good. If we’re not challenging each other to think outside the box, then what’s the point of creating art?”

On being socially and environmentally conscious

“I think that every single designer needs to be aware of how many of the things that they’re making already exist in landfills. We have a responsibility to only bring things to life that are going to live extremely long lives. For example: A lot of people are like, ‘Oh, it’s vegan leather’—well, vegan leather is plastic, and plastic breaks. It’s not good for clothes, there’s no longevity. I want to always challenge my fellow designers, creative people, and really people of all industries to say: If you’re going to be manufacturing these things, how can these things leave a positive impact? Not just a neutral impact or a negative impact—a positive impact.”

“I’m inspired by anything black.” —Shanel Campbell, founder of Shanel

Being inspired by her community

“I’m inspired by anything black. Black artists, musicians, activism. James Baldwin, Angela Davis, David Hilliard, and Nina Simone—they inspired a project I just did, where each one inspired a look, but you wouldn’t know from looking at it. I’m not trying to be so straightforward. If that were the case, I would just take my research and put it on a graphic T-shirt. The thing that informs all of my work is the black experience. That’s just how my brain works, I can’t help it. It’s exciting to know that some people get the reference, no matter how secretive or subtle it may be.”

On standing out in the crowd

“At this point, there are so many designers. The industry is crowded. I think you have to have a message for people to want to pay attention to—not just initially but keep paying attention. Like, ‘Oh, there’s more to this person. They have certain systems they’re trying to dismantle, or they create new visuals that may advance black art.’”

On bringing your whole self to your work

“A black woman or man in any field doing anything, it’s always done through their blackness. There’s no way you can turn that off or pretend you don’t notice. And if you don’t notice it at first, you’re going to find out.”

“It’s bigger than you, it’s bigger than us.” —Lizzy Okpo, cofounder of William Okpo

On changing the narrative

“Our culture is heavily embedded in our brand,” says Okpo. “Darlene and I always go back to where we grew up and how we were raised. We’re cautious about telling a story of growth and not just the struggle. I think politically we try to be the representative of what it means to be black and progressive in a very unapologetic way.”

On building each other up

“Politically, it’s really important for us to represent the importance of community building among women. We find ourselves working with women, women of colour specifically—female photographers, female creative directors, women from all [specialities]—that’s important for us because so often I feel like women are not represented, even in the fashion industry, the way that they should be. Working with youth is another thing that’s important for Darlene—she’s an educator outside of being a designer, so I think she feels growing up here that our youth is often forgotten about and we need to start there.”

On listening to your community, always

“A few years back, when we had a shop, we hosted an event at the height of police brutality within black communities. It was us gathering to talk about what’s happening in our everyday lives or the struggles that we’re [all] facing. We can talk about fashion all day, but what matters is what’s happening within our communities.”

To keep things in perspective

“It’s important for designers to work for a bigger purpose because fashion is so small. If you remove the social aspect of it and if you remove the day-to-day lifestyle of it, then we’re just left with a pair of pretty shoes—and who cares? That’s so disposable. You have to tell a story…you have to touch people beyond yourself. It’s bigger than you, it’s bigger than us.”

Mrs Vicky m Bournel has made this magazine proud. She is not only an Author from America for Lakkars Magazine she is the Chief Editor of Lakkars Magazine for the articles.