This French Artist Transformed Her Illness Into Art

Prune Nourry is a contemporary Amazon. This modern-day female warrior survived her battle against breast cancer, transforming her illness into art. After being diagnosed in 2016 at the age of 31, the NYC- and Paris-based French artist decided to understand her disease in order to heal and regain control over her suffering, turning the camera on herself and becoming the subject of her own work – a challenging feat for someone used to being behind the lens. Her intention initially wasn’t to make a film, but to be active and think about something else, to no longer be a passive patient. “Art is all about the process,” she states. “Most of the time, you don’t know where it’s going to lead you. You just start doing things and then you see. Meeting people along the way feeds your creativity. You never know exactly where you’re going to arrive before you do the whole journey.”

As filming progressed, a series of links between Nourry’s cancer and her oeuvre appeared, as if somehow her subconscious had known all along and made her create art over the years that would help her heal herself. Chemotherapy and freezing her eggs resonated with her “Procreative Dinners” (2009), where she had designed a meal with a chef and scientist that mimicked assisted reproduction. In-vitro fertilization became the aperitif and the choice of the child’s sex the main course. Eight years ago, her research on fertility led her to film women freezing their eggs. Covered in acupuncture needles, her sculptures for the 2016 exhibition “Imbalance” focusing on the qi and balance inherent in traditional Chinese medicine contrasted with an imbalanced China in terms of pollution and health. She recalls, “I was the most imbalanced of all the pieces because I had no hair, as I was undergoing chemotherapy.”

One day at The Met in New York, Nourry stumbled on a marble statue of an Amazon – a female tribe from Greek mythology who amputated their right breasts to become better archers – gazing serenely at her injury, which inspired her to make her own five-meter-tall Amazon sculpture that she transported on a barge on the Hudson River at the end of her treatment, lit the incense sticks enveloping it in a purifying ritual, and severed the breast with her sculptor’s tools as a symbol to mark her return. She notes, “From a sculptor, I had become a sculpture in the hands of the surgeon during reconstructive surgery after a mastectomy, and now I was getting back to being the sculptor.” Her hospital visits gradually turned into an artistic project, leading to her nonfiction feature debut, the documentary Serendipity, which premiered at the 2019 Berlin Film Festival and opened the MoMa DOC Fortnight Festival and Tribeca Film Festival in New York.

The first French artist to exhibit at Le Bon Marché department store in Paris last year, Nourry displayed a series of emblematic works created during the COVID-19 lockdown, including the monumental installation “Amazone Érogène”, a four-meter-diameter, breast-shaped wooden target at which 888 suspended arrows were pointed. “It’s a work between life and death, between Eros and Thanatos,” she explains. “The cloud of arrows can be seen as the disease attacking the breast, but it can also be seen as sperm heading towards the ovum, towards fertilization, towards life. There is also the idea that within the disease, there is also eroticism because we are attacking areas that are considered to be a woman’s main assets, but it is also a way of showing that scars are a marker of history, like tree rings. They partly tell the story of a person and are an integral part of their beauty. It’s true when we’re sick, we’re in the fight against the disease, but there’s also the idea of fertility, how in the disease, we can find creation and life. Even from a body that’s attacked and repaired, there is a promise of life.” Her documentary and artworks saved her, becoming a form of catharsis for her and other women with breast cancer, as she put her creativity at the service of healing. She then sold those arrows to fund the free distribution of 20,000 copies of her book Aux Amazones to women fighting cancer. A touching and inspiring account of her illness, it contains a foreword by Angelina Jolie and contributions from a psychiatrist, oncologist, radiotherapist, plastic surgeon and acupuncturists.

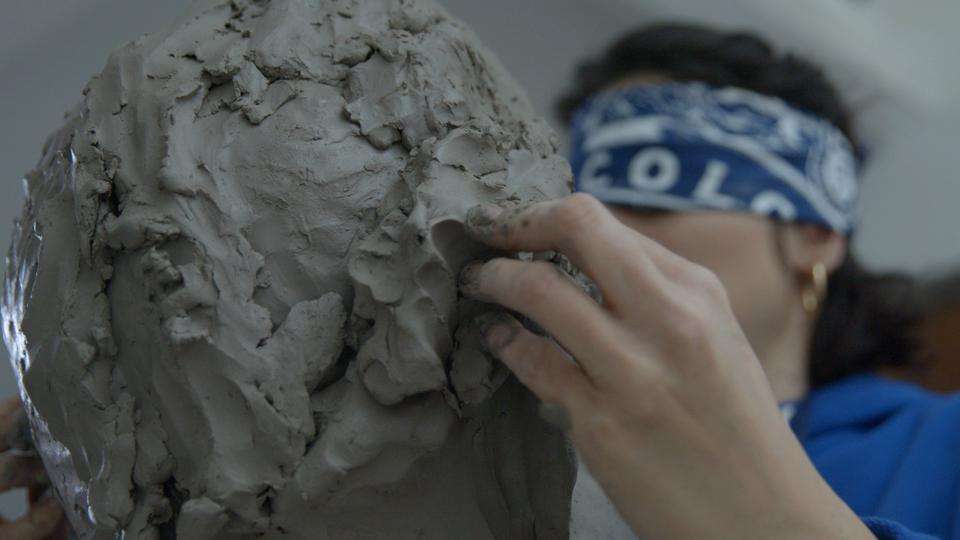

The sense of touch has always been fundamental to Nourry, who thereafter turned her attention to the visually impaired. “We share the same importance of touch,” she says. “As a sculptor, my hands are the continuity of my eyes.” After her exhibition “Catharsis” at Galerie Templon in Paris in 2019, in which she reappropriated her body and femininity, she returned to the gallery two years later with her “Phoenix Project” solo show inspired by the myth of the fabled fire bird rising from its ashes. Reviving the art of portraiture, she hand-sculpted portraits of eight visually-impaired models who posed in her studio, while blindfolded herself. She didn’t see her subjects or sculptures either before, during or after each session, imagining their faces instead through touch and listening to their life stories.

Fashioned from clay that was molded and cast, the eight sculptures were then fired by potter Jean-Pierre Benincasa in central France based on the 16th-century Japanese raku technique, which, glowing hot from the kiln, were immersed in wood ash and allowed to smoke. The thermic shock exposed each piece to extreme stress and resulted in crackle and surface effects that appeared randomly. Recorded conversations between Nourry and her models from the sculpting sessions were played above each piece, giving the viewer insight into the complicity between artist and model in the studio. Tactile works on paper embossed by Parisian printing house Laville Braille that depicted the subjects’ hands – their lifelines acting as symbolic portraits – were displayed, accompanied by a short film with audio description by Vincent Lorca about the exchanges between Nourry and the models, without showing their faces or the final works.

Presented in total darkness, the exhibition was adapted according to standard guidance systems for the blind, with visitors self-navigating. It symbolized the power of resilience and renewal and revealed her subjects’ capacity to integrate into society after their blindness, overcoming their disability through professional or voluntary work, and perhaps also marked her own renaissance following her illness. “It’s the idea of how you transform a handicap into a strength,” she discloses. “I’m getting back to the relationship between the model and the artist in the studio. However, I sculpt not with my eyes, but with my touch to try to feel the expression of their faces, which is super intimate. It’s very strange, especially during COVID-19, when they haven’t been touched for a long time, where the fact of being touched is a question of life and death.”

Magazine launched for helping women for success. Lakkars has always served and worked efficiently towards women empowerment, we have blossomed into America’s most-read fashion magazine.