How a humble Black Country schoolgirl became Hollywood’s highest-paid actress

At the one end of Herbert Street lies the A41 Expressway, which now separates it from the green expanse of Dartmouth Park. At the other end is the service yard for a retail park.

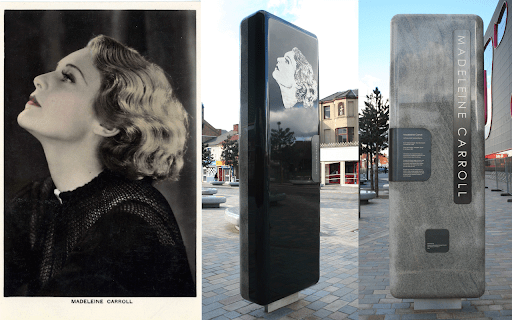

Then, halfway along this unassuming road of inner-city Victorian red-brick houses, something catches the eye. A blue plaque honouring the birthplace of Hollywood legend Madeleine Carroll.

West Bromwich-born Hollywood legend. Those are words you don’t hear very often. But while the word legend is sometimes bandied about rather casually, but when it comes to Madeleine Carroll it is almost an understatement.

Once hailed as the most beautiful woman in the world, she found fame as Alfred Hitchcock’s favourite ice maiden. Yet the elegant blonde with the cut-glass accent was actually born in a terraced house a stone’s throw West Bromwich town centre.

And 10 years after taking the lead role in the film What Money Can Buy, she was finding out for real as the world’s highest-paid actress.

Carroll made her name as the first of the cool, clever, quintessentially British blondes who were a key part of Alfred Hitchcock’s films. She was the first British actress to crack Hollywood, and in the 1930s the movie industry couldn’t get enough of her.

Yet when the Second World War came calling, she quickly abandoned the trappings of fame to join the fight for freedom. She gave up the glamour and glitz of Tinseltown to serve as a nurse with the American Red Cross, dedicating two years of her life to helping wounded servicemen and children maimed or displaced by war.

Edith Madeleine Carroll was born on February 26, 1906 at 32 Herbert Street, West Bromwich. Her father John was a professor of languages from County Limerick, while her mother Helen was French.

Graduating with a BA in languages at Birmingham University in 1926, it appeared that Madeleine would follow in her father’s footsteps. After completing her degree, she spent a year working as a French teacher at a school in Hove.

But during her time at college, she became active in the Birmingham University Dramatic Society, appearing in several productions, and decided that her natural habitat was the stage rather than the classroom.

Professor Carroll was not impressed, not viewing acting as a serious career. But her mother was more sympathetic, and supported Madeleine when she quit teaching to look for stage work in London.

After winning a beauty contest, the young hopeful landed a role with Seymour Hicks’ touring company, making her stage debut in The Lash at New Brighton in 1927.

It wasn’t a memorable part. The aspiring actress played the minor role of a French maid in the production. But after finally getting a taste of showbusiness, there was no stopping her. A few months later she appeared in the stage hit Mr What’s His Name, and several other West End productions followed. And movie stardom was just around the corner.

In 1928 she made her screen debut in The Guns of Loos, a lavish enough production, but one which didn’t quite live up to expectations. But while it might not have been the blockbuster many had hoped, Carroll made enough of an impression to land the leading role in the silent film What Money Can Buy a few months later. A remarkable feat considering she had only started acting professionally the year before.

But while stardom came swiftly, her rise to fame was far from effortless.

She was not a natural actress, her success stemmed from her work ethic and willingness to learn from established performers such as Hicks and Wolverhampton-born Miles Mander.

Her early work focused largely on her classic features, sophisticated demeanour, and that voice. She may have been a daughter of the Black Country, but she sure didn’t sound like one. Her finely honed vowels went down a storm with the Americans as the film industry made the transition to ‘talkies’.

But it was her appearance alongside Mander, son of Wolverhampton industrialist Theodore Mander, in The First Born that would truly propel her career into the stratosphere. Mander played philandering politician Sir Hugo Boycott, and Carroll his kindly but long-suffering wife. Not only was the film, co-written by Mander and Alma Reville, critically acclaimed, it also introduced Carroll to Reville’s husband Alfred Hitchcock.

A string of roles followed in quick succession, and Carroll’s intellectual background set her apart from many of contemporaries of the time.

She went to France to make Not So Stupid in 1928, before returning to the UK for The Crooked Billet and The American Prisoner in 1929.

In 1930 she starred in the controversial film Young Woodley, about a public schoolboy who falls in love with his headmaster’s wife.

By this time, she was firmly established as Britain’s most successful actress, but she stunned the world of entertainment in 1931 when she announced the end of her film career after marrying Capt Philip Astley.

They were not an obvious pairing, the glamorous screen vixen and the big-game hunting estate agent who served with the King’s Guards. Their marriage lasted eight years, but the Carroll’s retirement proved even briefer. Demand for her services was just too great, and a year later Gaumont-British made her an offer that was just too lucrative to turn down.

She had a big hit with I Was a Spy in 1933, which won her an award as best actress of the year. The following year she co-starred with Franchot Tone in The World Moves On, before returning to Britain to play Queen Caroline Matilda in the 1935 film The Dictator.

But it was her role in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1935 film The 39 Steps that would come to define her career. The film proved to be a sensation, and so did Carroll, who was hailed by the New York Times for her “charming and skilful” performance as the cold, aloof but alluring leading lady.

Hitchcock wanted to reprise her double act with Robert Donat, who played the raffish hero Hannay in The 39 Steps, the following year in his new film Secret Agent. However, Hannay was suffering health problems, and she was instead partnered with John Gielgud. In between the films she made a short drama The Story of Papworth.

By now, her career was at its zenith, and she became the first British actress to be offered a major American film contract. She accepted a lucrative deal with Paramount Pictures, initially for one year, but later extended to five, and was cast opposite George Brent in The Case Against Mrs. Ames in 1936. followed the same year by The General Died at Dawn. She also took the female lead in Lloyd’s of London the same year, before teaming up with Dick Powell and Alice Faye in On the Avenue in 1937.

By this time the films were coming thick and fast. She played Ronald Colman’s love interest in the 1937 box-office success The Prisoner of Zenda, and the following year played opposite Henry Fonda in Spanish Civil War movie Blockade. She also made some comedies with Fred MacMurray in Cafe Society and Honeymoon in Bali (1939).

She was also, by this time, the highest paid actress in the world, raking in $250,000 in 1938 alone – that’s roughly equivalent to £3.6 million at today’s prices.

She starred alongside Douglas Fairbanks Jr in the 1940 film Safari, and then teamed up with Gary Cooper again in North West Mounted Police. She played Bob Hope’s love interest in the 1942 movie My Favorite Blonde. But by this time, events back home across the Atlantic had caused her to take stock of her career and radically reassess her priorities.

In October, 1940, Madeleine’s sister Marguerite was in London when she was killed by a German air attack during the Blitz. Her death had a profound effect on Madeleine, and in 1943 she swapped Hollywood for a field hospital when she joined the American Red Cross as a nurse, adopting a pseudonym to avoid publicity.

In 1944, having become a naturalised US citizen, she went to serve in the American Army Air Force’s 61st Station Hospital in Foggia, Italy. Here she would tend to airmen who had been wounded while flying out of area’s air bases. It was no easy posting, as her location put her in the line of fire of passing troop trains. She earned the rank of captain and received the Medal of Freedom for her nursing service. She also received the French Legion of Honour for her work during the war, liaising between the forces of the US Army and the French Resistance.

She initially returned to Britain after the war, shooting the movie White Cradle Inn on location in Switzerland. She then went back to the US where she appeared in An Innocent Affair. But by this time her star had faded, and she found her humanitarian work more rewarding and went to work for Unicef. Her last film was The Fan in 1949.

After the war, she began working with the rehabilitation of concentration camp inmates, and als presented a radio programme which aimed to improve friendships between the French and Americans.

Her contribution to the film industry was recognised with her induction into the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960, with a star located at 6707 Hollywood Boulevard.

A commemorative monument and plaques were unveiled in her birthplace, West Bromwich, to mark the centenary of her birth. Her story is one of rare courage and dedication when at the height of her success she gave up her acting career during World War II to work in the line of fire on troop trains for the Red Cross in Italy after her sister was killed by a German air raid – for which she was awarded the American Medal of Freedom.

During the war, Carroll also donated a property she owned, a château outside Paris, to house more than 150 orphans, and arranged for groups of young people in California to knit clothing for them. Allied Commander Dwight D Eisenhower remarked in private that, of all the movie stars he met in Europe during the war, he was most impressed with Carroll and Herbert Marshall who worked with military amputees.

Carroll, who was married and divorced four times, formed a production company with her third husband, the French producer Henri Lavorel, which made a number of documentaries to promote peace. One of them, Children’s Republic, was shown at Cannes Film Festival. She told the Christian Science Monitor that “wars are started at the top but can be prevented at the bottom, if all men and women will rid themselves of distrust and suspicion of that which is foreign.” The film was made in a small orphanage in Sevres, a suburb six miles from the centre of Paris, and it told about the devastating impact of the war on the lives of children. It received a worldwide audience, and led to a mass fundraising drive to pay for artificial limbs for wounded children.

From then on, she largely retired from public life, aside from the occasional appearance on television and radio until the mid-1960s.

She moved to Paris, and later to Spain, where she shared an estate in Marbella with her mother and daughter. Carroll died on October 2, 1987 at the age of 81, having suffered from pancreatic cancer.

While her work as a film star, humanitarian campaigner and war hero earned her honours around the world, very little was done to honour Carroll in her home town. At least until the late historian Terry Price took her case up in the early 2000s.

In 2006 to mark the 100th anniversary of Carroll’s birth, Mr Price helped organise an event commemorating her life at The Public arts centre in West Bromwich. The same year he personally financed the blue plaques which adorn her birthplace in Herbert Street, and the house in Jesson Street where she grew up.

But it was in 2007, after years of campaigning by Mr Price, the actress finally got the recognition he felt she deserved, when a monument to her life was erected in the town centre.

From the humble backstreets of the Black Country, to the glitz of Hollywood, and the battlefields of the Second World War, Madeleine Carroll enjoyed the most remarkable careers.

And it is fair to say she probably proved her father wrong.

Mrs Vicky m Bournel has made this magazine proud. She is not only an Author from America for Lakkars Magazine she is the Chief Editor of Lakkars Magazine for the articles.

1 thought on “How a humble Black Country schoolgirl became Hollywood’s highest-paid actress”

Comments are closed.

Top site ,.. amazaing post ! Just keep the work on !