South Korean Women Start Their Own Business

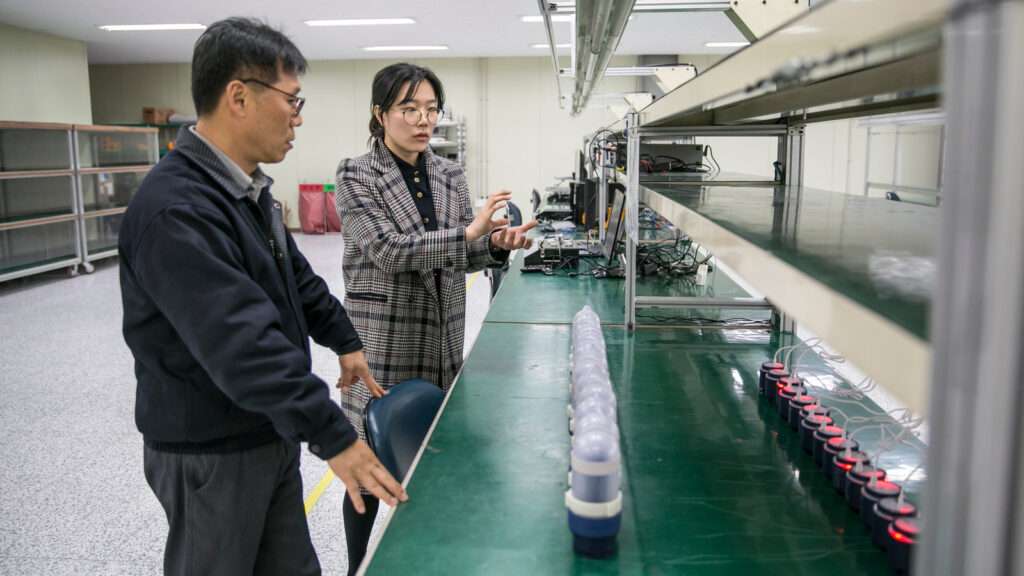

At first glance, Energy Nomad appears to be a typical South Korean company: Just about everybody who works there is male.

Crusty engineers, mostly in their 40s and dressed in matching dark jackets and black pants, hover over its production lines in a factory outside Seoul, or work at nearby desks. The sole exception is one young women, who deferentially bows her head as a senior manager directs her into a meeting room.

But at this start-up, looks can be deceiving. The lone woman, Park Hye-rin, is the boss. She founded Energy Nomad in 2014.

“I may be able to encourage the next generation of women” said Ms. Park, 33. “More young women might join me in this community of the future.”

Ms. Park is one of a new wave of Korean women who are starting their own companies. Frustrated in their climb up the corporate ladder in a male-dominated business culture, they choose to find another way up.

“In education we are equal to men, but after we enter into the traditional companies, they underestimate and undervalue women,” said Park Hee-eun, principal at the venture-capital firm Altos Ventures in Seoul. “Women are disappointed with the working culture, so they want to make their own companies.”

In 2018, more than 12 percent of working-age women in South Korea were involved in starting or managing new companies — those less than three and a half years old — a sharp increase from 5 percent just two years earlier, according to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. In Japan, where women face similar biases, only 4 percent are starting companies.

Similarly, a Mastercard report on 57 global economies last year said that South Korea showed the most progress in advancing female entrepreneurs, and that more women than men had become engaged in start-ups. Government statistics also show that a rising percentage of new companies, about a quarter, were started by women last year.

The trend could reshape a corporate world where discrimination against women is deeply entrenched. South Korea has been a marvel of economic progress over the past 50 years, transforming from one of the world’s poorest countries into an industrial powerhouse famous for its microchips and smartphones. But notions of women’s role in society have changed slowly, often trapping them in poorly paid jobs with little chance of advancement.

Only about 10 percent of managerial positions in South Korea are held by women, the lowest among the countries studied by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, while the gap in pay between men and women is the widest.

These biases infect the start-up sector, too. Building a new enterprise is a risky endeavor in any circumstances, but South Korean women often are not taken seriously by male bankers, executives or even employees.

“You have to put extra effort into being a female entrepreneur,” said Kim Min-kyung, founder of a personalized lingerie company, Luxbelle.

Ms. Kim, 35, was undeterred. By the usual standards of success in South Korea, she had already made it big, landing jobs at affiliates of the Samsung business group, among the most coveted positions in the country.

But she felt unappreciated within Samsung’s bureaucracy. Though Ms. Kim never faced overt discrimination there, she said, she also knew she would eventually smack into a very low glass ceiling.

“I thought I would not have a future as a woman at a more traditional company,” Ms. Kim said. “I thought I would not get a top position, so I had to go out and start my own business, sooner rather than later.”

A start-up, she added, “is my company, and I can do whatever I want.”

Ms. Kim quit Samsung in 2014 and started Luxbelle with a partner a year later. Its website guides women in choosing and fitting lingerie, under the brand name Sara’s Fit, which they can then buy online. From a bare-bones two-room office in a hip neighborhood in Seoul’s Gangnam district, Ms. Kim has tackled almost all aspects of the business — designing the lingerie, managing the website, raising capital and personally measuring customers who stop in for some offline attention.

‘There’s this notion of a superwoman’

This type of entrepreneurship was once a rarity in South Korea, for either sex. Still-conservative families tend to press sons and daughters to seek more predictable employment within the government or at the nation’s big enterprises. Venture capital was scarce in a financial system built to funnel funds to the large conglomerates, called chaebol, that dominate the economy.

The situation began to loosen up during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. Entrepreneurship became more socially acceptable, even cool, and money became more widely available.

Social attitudes toward women are changing, too, though slowly. It remains common for parents and spouses to expect wives to carry the burden of child care and household responsibilities.

However, Lee Ji-hyang, an entrepreneur, said she believed South Korean society was becoming more understanding of women’s professional goals.

“There’s this notion of a superwoman who can perfectly juggle family and work life. She was the role model,” she said. “But now there’s also a notion that women handle too much.”

Ms. Lee, 28, started her company, Mark Whale, last year to market fragrances that she develops and mixes herself. From a desk at an all-female incubator in Seoul, she sold her initial product, a leather car freshener, mostly online.

“My husband and I are planning our future together,” Ms. Lee said. “When I was at a crossroads between getting a job and starting a business, I was encouraged by my husband.”

“I definitely think I’m part of the trend,” she added.

The government has stepped in to help. It wants more women to enter the work force as South Korea’s population ages and it looks for ways to keep its economy growing. According to the ministry for start-ups, the government earmarked $470 million to support companies run by women in 2019, 18 times the 2015 total.

Public institutions also budgeted $7.6 billion to buy goods and services from women’s firms this year. Since 2014, the state-linked Korea Venture Investment Corporation has allocated $35 million of government funds to venture capital firms to invest in start-ups founded by women.

But female entrepreneurs still face hurdles in a business world where hardly any women are senior bankers or executives.

Kim Min-kyung found herself in the uncomfortable position of discussing Luxbelle’s lingerie with venture capitalists who were almost exclusively male. “They don’t even understand that fitting a bra can be a business,” she said.

She was rejected so often, she said, “my confidence hit rock bottom.”

The networking and schmoozing that entrepreneurship often requires can be no less awkward. One of Ms. Kim’s investors, an arm of the Lotte business group, offered her office space at a business incubator. The male manager joined the other entrepreneurs there in after-hours beer-drinking outings, a common practice for office colleagues in South Korea. But Ms. Kim wasn’t invited, and was too shy to ask to go.

“If female entrepreneurs want to network with different people, they have to be assertive enough to put themselves right in the middle of the boys’ club,” she said. “It takes a lot of courage among female entrepreneurs to do that, and they find it difficult to start that process.”

Managing male employees can also be tricky, as Jihae Jenna Lee discovered. After more than a decade on Wall Street, Ms. Lee returned to South Korea and in 2015 started AIM, which offers computer-driven financial advice. Now managing $40 million from 4,200 investors, Ms. Lee and her six-member team operate the service — which she markets as a “hedge fund brain packaged as a mobile app” — out of a WeWork office in a popular shopping district of northern Seoul.

In 2016, she hired a senior manager from a Seoul brokerage firm to augment her start-up’s local expertise. But, Ms. Lee said, he had trouble accepting the fact that his boss was a woman. On one occasion, Ms. Lee felt he undermined her authority in front of the entire staff. When she raised the issue with him privately, she said, he apologized but then made his discomfort clear.

“He said, ‘I think I’m not seeing a woman boss,’” Ms. Lee, 39, recounted. The employee left after only three months.

Many men in South Korea “are not used to seeing a women in power, women who are making decisions, or women as a partner,” Ms. Lee said. “They’ve only seen probably one female executive in their whole lifetime.”

Ms Jung So-min is an Author from south Korea for Lakkars Magazine she is the Head of East Asia.